The annals of history are replete with stories that, if told without context, would seem more at home in a dystopian novel than in the documented ledger of past events. One such narrative that might strain credulity concerns the covert operations conducted by the U.S. government - operations which involved the unsuspecting public and the deliberate release of bacteria. This is not the stuff of conspiracy theories; these events are part of a sobering reality that unfolded over several decades in the 20th century.

The focus of this exploration is an examination of these little-known experiments, specifically the 1966 operation in the New York City subway system. The clandestine nature of these tests, the implications of their execution, and the ethical quandaries they present offer a window into a time when Cold War paranoia eclipsed the rights and well-being of individuals.

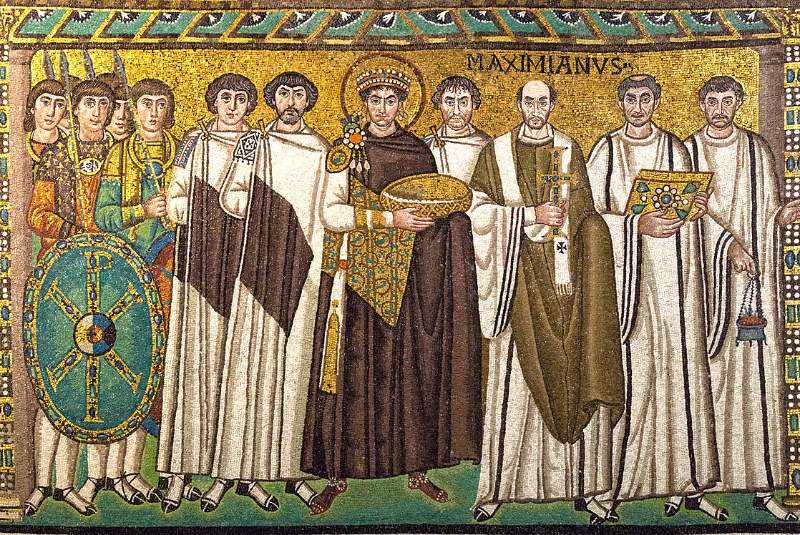

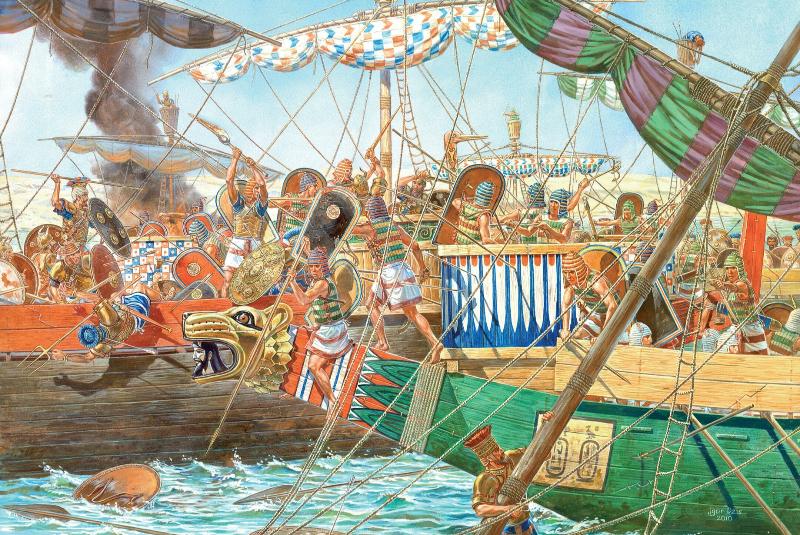

During this period, the specter of biological warfare loomed large. The concept wasn't new—bio-warfare had ancient roots, with historical accounts of besieging armies catapulting plague-infected corpses over city walls or poisoning water supplies. However, it was the scientific advances of the 20th century that transformed biological agents into weapons of unprecedented potency.

The subway experiment in New York was part of a larger program called Operation Large Area Coverage, which was designed to evaluate the United States’ vulnerability to a biological attack. The U.S. Army’s interest in biological warfare had been piqued by reports of Japanese bio-warfare activities during World War II and later by the potential for Soviet biological weapons during the Cold War.

The operation was startlingly straightforward: scientists released bacteria into the subway system to observe how they spread through the network and the city. The bacteria were placed inside lightbulbs, which were then covertly broken, releasing the bacterial agents into the subway's environment. This activity was underpinned by the assumption that the bacteria were harmless, a supposition that would later be questioned.

Air sampling devices were positioned to gather data on the dispersal patterns of the bacteria. This was not an isolated incident but part of a series of biological and chemical tests that spanned two decades. Over 240 such experiments were reportedly conducted, none of which were disclosed to the public or, it seems, subject to any form of consent by those potentially affected.

The very notion of conducting such experiments on an unknowing populace seems to fly in the face of ethical standards, not least the Nuremberg Code. Drafted in the wake of the atrocities of World War II, this set of research ethics principles for human experimentation mandates voluntary, informed consent from all participants.

What drove these scientists, these agents of the military, to bypass such ethical considerations? Was it the urgency of the Cold War, the pressure of staying a step ahead in a perceived arms race of biological weapons? Whatever the motivation, the experiments proceeded without the knowledge or consent of the American public.

However, the plot thickens upon closer inspection of the bacteria used. Initially believed to be benign, some of the bacterial strains would later be identified as potential pathogens, implicated in significant food poisoning outbreaks. The assertion by the army scientists that the bacteria were harmless was not just overly optimistic but possibly negligent.

It is essential to contextualize these actions within their time. The Cold War was an era of suspicion, where the threat of annihilation hung like a specter over the world’s head. In the United States, this fear manifested in a race for superior weaponry and defense mechanisms. The government, obsessed with national security, often pursued these goals at the expense of individual liberties and ethical practices.

Returning to the New York subway experiment, one can only surmise the potential health impacts on the population. The bacteria were released during peak hours when the subways were crowded, and the constant movement of trains would have facilitated the spread of these organisms throughout the system and possibly beyond. The likelihood of someone being infected was not trivial; however, the exact numbers remain elusive.

Following the experiments, it was noted that few passengers seemed alarmed by the occurrence, with most continuing their day unphased. But this nonchalance belies the gravity of the situation. The army’s own reports highlighted a terrifying outcome: should a real biological attack occur, the spread would be rapid and devastating. This chilling assessment underscores the potential danger of the experiments themselves.

Scrutinizing the Germ Warfare Tests

These operations open a Pandora’s box of questions. First and foremost, there is the matter of public trust. How can a government reconcile the need for national security with the imperative to protect the rights and health of its citizens? The balance is delicate and fraught with moral ambiguity.

Furthermore, the use of pathogens, even purportedly nonpathogenic ones, in a public setting without safeguards raises the specter of unintended consequences. Pathogens can mutate, and their effects on diverse populations with varying levels of health and immunity are unpredictable. The assumption of harmlessness is a gamble, one that could result in unforeseen outbreaks and public health crises.

Beyond the immediate physical risks, there are profound ethical implications. The use of citizens as unwitting test subjects, even in the name of national security, violates fundamental human rights and personal autonomy. It is a form of utilitarian calculus that places the perceived greater good over the rights of individuals, a perspective fraught with peril and subject to egregious missteps.

These experiments also bring into focus the shadowy world of government secrecy and the extent to which operations are shielded from public scrutiny. Transparency is a cornerstone of a democratic society, and when actions are taken in secret, especially those with potential health implications for the public, it undermines the trust between government and governed.

Lastly, there is the issue of accountability. To this day, it is unclear what, if any, repercussions were faced by those responsible for these tests. Without accountability, there is little to deter similar actions in the future, creating a precedent that could be invoked for further unethical practices.

The germ warfare tests of the mid-20th century, particularly the 1966 New York City subway experiment, reveal a troubling aspect of American history. The drive to protect the nation resulted in actions that, by today's standards, are deeply problematic. These events serve as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the importance of ethical oversight, transparency, and the delicate balance between individual rights and national security.

This history also compels us to ask difficult questions about the role of government, the boundaries of ethical conduct in research, and the nature of consent. As we look back on these events, it is crucial to extract lessons that inform current practices, ensuring that the rights and well-being of the public are never again compromised in such a manner. The shadows of the past must serve to illuminate the path forward, guiding us toward a more conscientious and accountable approach to security and scientific inquiry.